I

KEMPSHOTT PARK

Background, Acquisition, Projection

The Kempshott Estate was one of the earliest country seats taken by the eldest son of King George III. With negotiations having begun in 1788, George Augustus Frederick, Prince of Wales, bestowed royal patronage on Kempshott in 1789 by becoming the lessee at the age of twenty-seven. The Prince's position as a Kempshott newcomer at this time was not exclusive, however, for the lessor and lord of the manor, John Crosse Crooke, had completed his purchase of the estate only on 5 July 17 88. 1 At the time Mr Crooke, of St. Mary le Bone, Middlesex, was leasing Stratton Park, five miles south-west of Kempshott, from the Duke of Bedford and, notwithstanding his acquisition, appears to have continued his residency there until 1789. 2 Reasons for his apparent non-occupation of Kempshott are conjectural. Perhaps the seat's immediate purpose was to be that of an income-producing investment, although eventually retiring there in 1803. Here, Crooke had found a prospective, eager royal tenant. Conversely, if his intention was to reside at Kempshott then sufficient time seems to have been allowed, some eight months, for the preparation of the house - and perhaps the immediate grounds - to his and his wife, Elizabeth's tastes before the expiration of his Stratton Park lease, prima facie

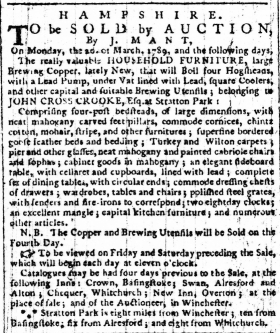

March 1789. The Prince of Wales' very timely interest in wishing to take the seat, however, may have confounded such plans, resulting in Crooke deciding to raise his own status and that of Kempshott by becoming landlord to the future King George IV. Here, even if his lease to Stratton had expired at some point in 1788, remaining there for as long as necessary would have been achieved via princely influence - the Duke was a Whig confidante of the Prince. This idea may be supported by reportage of the Duke's brother, Lord John Russell, taking 'possession of that mansion [Stratton Park] as soon as Mr Crook[e] leaves it', suggesting a degree of flexibility in Crooke's favour. Regardless of his intentions, though, Crooke's furniture and effects were auctioned in situ on 2 March, 1789. Whether he then remained in Hampshire is unknown, but at some point between 1789 and 1797 he took Hallingbury Place, Bishop's Stortford, in Hertfordshire.3

Stratton Park, Hampshire, c.1930

Image reproduced by courtesy of Lost Heritage - England's Lost Country Houses

Kempshott's 1,040 acre estate had been an excellent purchase for John Crooke at £14,670, the consideration having fallen from £15,842 during the eleven months of an exceptionally short occupation by the previous owner, James Morley, a 'nabob' of the 'Honorable The English East India Company', his service having totalled thirty-eight years. Mr Morley had been the highest bidder for the Kempshott Estate at a 'Public Auction at Garraways Coffee House in Change Alley London, on Friday the twenty fifth day of May [1787]'. The death of Morley's wife, Anne, shortly after childbirth, on 24 December, 1787, aged 30, possibly was the catalyst for his decision to sell. He then retreated to his Town residence at Caroline Street, Bedford Square, Middlesex.4 The later negotiations between Mr Crooke's solicitor and the Prince's solicitor, Charles Bicknell, [were quite lengthy and] lasted for up to one year. An agreement was then reached to lease Kempshott House and 350-450 acres of the surrounding Kempshott estate, commencing in late 1789. The yearly rent is estimated at c.£600, with taxes thereupon estimated at eighteen per cent. This is based on the rent paid by the Prince for the much larger Northington Grange, Hampshire, together with 660 acres, taken in 1795, which was £900 p.a., with taxes at £163 6s 5d. The Prince's legal fees for Kempshott amounted to £14 8s.10d.5

Besides Charles Bicknell, officials of the Prince's household involved in negotiating the lease and managing Kempshott will have included his Chamberlain, George James, fourth Earl and first Marquis of Cholmondeley; his Treasurer and Secretary, Henry Lyte, 1787-91, and Colonel [later General] Samuel Hulse, from 1791; his Solicitor-General, Arthur [later Sir] Leary Piggott, 1786-93, and John [later Sir] Anstruther, 1793-95; his Master of the Household, J. Kemeys Tynte, 1791, and John Byde, 1795; the Auditor and Secretary of the Duchy of Cornwall, Henry Lyte, to 1791, and Captain [later Admiral] John Willett Payne, from 1791.

Kempshott House was no more than fifteen years old, its construction the work of Philip Dehany (c1720-1809), James Morley's predecessor. Dehany, inter alia, was a Hampshire magistrate, whose fortune, very possibly, had partly derived from family plantations in the West Indies. For nearly two years, from 1778 to 1780, he had been the second member for the pocket borough of St. Ives, Cornwall - the first member at this time being Sir Thomas Wynn, third baronet, and [from 1776] first Baron Newborough - via a parliamentary by-election held on 26 December 1778, succeeding Adam Drummond. Dehany's sponsor is likely to have been his Hampshire neighbour, the Duke of Bolton, a major landowner in the West Country and lord of one of the manors of St. Ives. Wynn and Dehany were succeeded by William Praed and Abel Smith, following the General Election on 11 September 1780. Dehany was a keen sportsman, too, being a member of the Hambledon Cricket Club and 'a great cricketer'. A leading patron of the game, he was elected to the 'committee of the noblemen and gentlemen, who met at the Star and Garter, in Pall-Mall, in February 1774, to settle the laws of cricket'.

Following his tenancy of the Earl of Portsmouth's seat at nearby Farleigh Wallop, Dehany had purchased the Kempshott Estate in 1773 from Anthony Burleton, the owner since 1771, having succeeded Dorothy Lee (nee Pincke), niece of Henry Pincke, from whom she inherited the estate in c.1770. Dehany's vision of a new house for Kempshott, with 'an extremely commodious interior', was achieved shortly after his purchase when he '... pulled down the old house, and built a handsome, large mansion of brick, in its stead, on a gentle knowl, to the south of the [Winchester to London] turnpike road, and very conspicuous from it ...'.6 Such an expensive undertaking was typical of the changing tastes of society and the increase in disposable incomes and status for many of the landed gentry of this period - this increase in wealth being reflected also in the popularity of private commissions for paintings by leading artists, successive lords of Kempshott being no exception. Philip Dehany commissioned Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788) for a family portrait: "Mr and Mrs Philip Dehany". Today, this outstanding work is included as part of a private collection. Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792) painted the individual portraits of the young John and Elizabeth Crooke. Nineteenth century mezzotints of the Crookes, by G.H. Every, after Sir Joshua Reynolds, were published in 1864. (The National Portrait Gallery, London, purchased them in 1966, and they can be viewed on the NPG's website under refs. D1603 / D1604).

Hampshire Chronicle Advertisement

For the Sale of John Crooke's Furniture and Effects

at Stratton Park on Monday, 2 March, 1789

During negotiations for the Prince's tenancy it was said that the arable land, meadow and woodland surrounding the mansion house did not meet with royal approval. The Prince and John Crooke, however, agreed to the engagement of a 'celebrated landscape gardener ... to form the plantations' and to create a Park from the 'several inclosures which then surrounded the house' - doubtless a principal reason for the lengthy negotiations.7 Crooke, of course, may already have commissioned landscaping, leaving the Prince to implement mutually acceptable embellishments. The landscape artist, from G.F. Prosser's 1833 description, almost certainly was Humphry Repton (1752-1818), whose first paid commission was at Catton Park, Derbyshire, in 1788. In 1805, he was to submit plans for a revised Marine Pavilion (then, Pavillon), Brighton, and which the Prince was to consider 'perfect'. Repton, in his inimitable style, would have prepared watercolours of the proposed alterations by means of perspective views furnished with flaps, designed to allow a comparison between the demesne in its unimproved and improved conditions. Repton usually acted as a consultant, with his work presented in a leather-bound 'Red Book', leaving others to execute his designs. In view of this commission, though, Repton is likely to have overseen the completion of Kempshott Park.

In the book 'The Destruction of the Country House', the editor, Sir Roy Strong, describes such outcomes thus: 'The finished park, though, would have been more than just a landscape providing commanding views across the countryside from the windows. It would have been an attempt to idealize the landscape. In the minds of all those who created or watched the creation of such parks, this made landscape gardening one of the fine arts. Much must have been spent on drainage and contouring, clearing and planting, with the aim of producing natural effects'.8

Kempshott's geographical feast began at the lodge-house, on the east side of the newly created Park, opposite the Kempshott turnpike gate, where, after a few hundred yards, a private road conjoined with an avenue crossing the Park. On each side of the avenue would have been picturesque views diversified by the likely presence of established and sapling oak, ash and beech trees, the avenue then ascending a small knoll to reach the south-east front entrance of Kempshott House. A flock of sheep and several head of deer are also likely to have animated the Park. The drive from the lodge-house was about one-third of a mile, ending with an immense contrast: the inviting mansion house immediately to the right; the eerie darkness of Kempshott Wood curving away to the left. The exit road, west side of the Park, swept away to the turnpike road.9 Further along was the stable block containing six stables, possibly with six and four stalls to each, a coach house for up to six carriages and hunting boxes with men's sleeping rooms over. Behind the stable block, to the south, were gardens of nearly five acres and enclosed by high brick walls. There was also a nearby orchard. The gardens may have contained, inter alia, fruit trees, a hot house, a melon ground and an ice house 'well planned and quite full'. A prestigious pinery is likely to have existed, pineapples having been imported from the tropics, grown under glass and fructifying every third year. Adjoining the gardens were paddocks of thirteen acres.

The Prince had now committed himself to leasing something akin to the following realty, the details having been taken from the earliest surviving survey to have included Kempshott Park, that of 1830, the Prince's detailed lease, should it still exist, remaining undiscovered:

Kempshott Park (151 acres: 2 roods: 39 perches)

Mansion garden, nursery, stable-yard etc. (5: 3: 23)

Kempshott Wood and Orchard (47: 3: 27)

Plantations (41: 3: 39)

Paddocks and Pasture (13: 0: 27)

Roads and Droveways (2: 1: 31)

Home farm, yard, garden, paddock, kennels, etc. (2: 3: 19)

Closes attached to the home farm (127: 0: 17)

(Only 2 closes are identifiable for 1788, 'Sullingers' and 'Bushy Plott')

Total acreages: 393 acres, 0 roods, 22 perches10

Today, Kempshott Park exists in the form of Basingstoke Golf Club. It extends into land that was part of the Dummer Estate in the eighteenth century, the village of Dummer also being the childhood home of Sarah, Duchess of York, in the twentieth century.

Kempshott House & Park, 1833, North-West Front, by G.F. Prosser

Embellishments in the Palladian style, including stucco, were added by

Edward Walter Blunt, following his purchase of the estate in 1832

The Prince had chosen Kempshott as a place he considered to be well-suited for pursuing 'country sports'. His visits to the Duke of Bolton, at Hackwood Park, and his participation in hunts staged by the Duke in this part of Hampshire, are likely to have constituted principal reasons for taking a nearby hunting-lodge. A further reason for his choice may have been connected with the Regency crisis of 1788-9, following short-lived concerns over the mental health of King George III. Statesmen in favour of the Prince of Wales taking, as they saw it, an indefeasible right to the Regency, notably Charles James Fox, the Whig Party leader [one of whose closest friends was the Duke of Bedford], were opposed by Ministers who maintained that it was for Parliament to determine who should be installed as Regent and on what conditions. Prime Minister Pitt, however, held that while the Prince should be appointed Regent, he should have limitations on his powers. The Prince of Wales and his supporters vehemently opposed this, among whom were many Hampshire magnates. At County Hall, Winchester, on 9 February 1789, at 12.30 pm, a meeting was held of 'Noblemen, Gentlemen, Clergy and Freeholders of the County'. The proceedings were opened by the Sheriff, who gave 'a short and pertinent speech, explanatory of the cause of [the] Meeting'. Sir Thomas Miller, of Froyle House, Hampshire, then rose, unequivocally gave his support to the Prince for an unrestricted Regency and begged leave to present an Address for the consideration of those present. Supporting speeches from other local notables followed. Many 'respectable characters' including the Prince's Kempshott neighbour, the Earl of Portsmouth, endorsed the Address. There were only two dissenting voices.11 With the nation being divided on the issue - and not without some strong hostility towards him - the Prince may well have decided that he could not afford to ignore such overwhelming camaraderie. By leasing Kempshott, he may have felt that he was among friends.

The prospect of a Regency government was strongly commented upon, also, in private correspondence circulating in Hampshire, not all of it so favourable toward the Prince. Lord Wallingford, heir to the seventh Earl of Banbury and a serving military officer, for example, informed his sister, with great concern, of his refusal to sign a petition supporting the Prince of Wales as Regent.12 He wrote again on 6 June 1788, referring to:

'...the blameable Conduct of the P[rince] of W[ales] & his Ducal Relations The Duke of G[loucester] has overcomed much mischief, & the family are all torn to Pieces - the disaffected, much dissatisfied by Reason of this M[adness?] not appearing at Court, & talk now of nothing But the Queen's Politics, for notwithstanding you hear of Gala's [sic] Balls, Entertainments etc. Things are far from being right.'13

A letter to the Archbishop of Castel, Ireland, dated 12 November 1788, written by an unknown correspondent over several days, and commenting on the King's position reads:

'... You probably have already heard, but not from better Authority, that the King is irrecoverably ill, I am told that his situation tho generally understood to be deplorable is not really known to many, that he has been totally & constantly irrational since the 5th Ins'[tant] & by Posability may live for years a Driveller ...'

The letter then refers to the inevitable dissolution of the English Parliament - but not the Irish Parliament - in the event of the King's death, citing various Acts to support this. It continues:

'... I kept this Letter open to learn ye Accounts of this Day's Packet, they confirm those of Yesterday ...'

'Mr Fox tho now in Italy most likely to be Minister possibly ye Prince of Wales Regent if his father lives'.

The prospect of a recovery for the King, however, is expressed in the closing stages of the letter:

'The King is by a second Dose of James's Powders supposed to be somewhat better, the special Messenger of the Day says much better on the Ninth Instant ...'.14

Writing on 26 December 1788, Lord Wallingford also comments:

'It is with much Confidence asserted that His Majesty will recover, tho we know for a certainty that Doctor Willis, and all the Rest of ye College disagree ? , & I tell you as a fact that her Majesty & the P[rince] of W[ales] & the D[uke] of G[loucester] are at variance about the Regency, & the Friends of his Highness say that the 'Q' is equivocal ...'

He makes two further observations in the same letter:

'... Mrs Fitz - has been offer'd 10,000 a year to go abroad, & her refusing, It was doubled, but she still persists In her Refusal - This I heard from her Confessor ...'

'... the Prince of W. is not upon Terms with Mrs F. about Letters he [wants ?] her to give up ...'.15

Lord Wallingford, without equivocation, was opposed to the Prince of Wales ever becoming Regent.

Part of Kempshott Park Today (Now Basingstoke Golf Club)

Photograph: Christopher Golding (October 2011)

The Prince, though, appears to have enjoyed the life of a Hampshire country gentleman, for by mid-1791 he had acquired the rest of the Kempshott Estate having leased Southwood, a working farm of some 600 acres. Negotiations with John Crooke again were protracted - draft contracts having been prepared in August 1790, with final contracts not appearing until April 1791. This apparent procrastination may be explainable, however. Hampshire folklore has alluded to Mrs Maria Fitzherbert having [officially] resided at a nearby property during the Prince's Kempshott tenancy - a cottage and a farmhouse, for example, have been mentioned at different times. Mrs Fitzherbert was somewhat more than just a close companion to the Prince, for they had secretly and illegally married in 1785, in contravention of the Royal Marriages Act, 1772. During preparation of the draft lease, it is feasible that Southwood's large farmhouse was re-evaluated as a potentially suitable residence for her. Its location was discreet yet sufficiently close to Kempshott House. If this were the case, then, more time will have been needed to prepare the property and the immediate grounds to Mrs Fitzherbert's taste, inevitably delaying final contracts. With a satisfactory refurbishment of Southwood Farmhouse, the property presumably would have been ready for occupation by April 1791, the date of the lease's engrossment. By contrast, the taking of a cottage on the estate would have been relatively speedy, uncomplicated and unlikely to have caused significant delays. Such a property, though, was unlikely to have been suitable for a person of Mrs Fitzherbert's standing. Speculation on the sitting tenant farmer's position is a little more tenuous. He could have been temporarily allotted, say, one of the tofts, the inducement being his future return to a substantially refurbished farmhouse.16

Southwood was situated in the parishes of 'Winslade, Saint Lawrence Wootton and Dean', to the north of the turnpike road, from Winchester to London, which ran through the estate. Included were '... the Barns, Stables, Outhouses thereunto belonging And also the Fixtures belonging to the said Messuage or Tenement and Premises ...'. The Prince would have acquired the exclusive right to '... hunt hawk fowl course shoot and sport in over and upon the said demised Lands and Premises at all seasonable times during the said Term doing thereby no wilful damage'. He would have been responsible for paying 'Rates Taxes Charges Payments Assessments and Impositions', as well as the Land Tax and the Landlords Property Tax. This will have included liabilities for money payments in lieu of tithes which amounted to five shillings per annum in lieu of the small tithes in kind - based on 160 acres surrounding Southwood Farm - with Winchester College taking nineteen shillings per annum in lieu of the great tithes. A further yearly sum of four shillings and sixpence also was payable to an unknown recipient. He had a duty to maintain the premises and the '... Hedges against the Turnpike Road ... to be cut level with the bank ... to mend gaps in the hedges or fences and not to cut any live wood from such hedges'. The Prince doubtless acquired responsibility for ensuring that '... the offices of Churchwarden Overseer Constable Tythingman Surveyor of Roads from time to time...' were discharged. The tenant farmer, almost certainly, was Henry Goodman who would have retained rights to '... fell saw and carry away timber and other trees using servants workmen horses carts and carriages'. He also had rights '... to plant trees layers and quicksets in the several banks or hedgrows belonging to the premises'. Doubtless he had certain shooting rights.17

Thomas Milne's Map of Hampshire (Detailing Kempshott), Published by William Faden, 20 Dec. 1791.

The Winslade and Dummer parish boundary can be seen clearly.

This version taken from 'Old Hampshire Mapped', and is by courtesy of Jean & Martin Norgate

With the Prince's additional financial obligations at Southwood, income from the farm, now his, must have slightly alleviated this additional burden.18 The rent paid to Mr Crooke for the farm is estimated at c.£300 per annum, and probably payable every quarter - on the feast days of saints, for example, the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary (25 March), St. John the Baptist (24 June), St. Michael the Archangel (29 September) and St. John the Apostle (27 December).19 The legal fees for drawing up and engrossing the lease amounted to five guineas (£5.25 GBP today).20 Southwood Farmhouse was built probably during the first half of the eighteenth century. It was made of brick, consisting of two storeys and an attic, the first floor being a string arrangement. The roof was tiled with flanking chimneys. There was a three-bay cast front with two three-light hipped dormer windows. Two three-light outer casements flanked the upper two-light and half-glazed central door with a plain rectangular fanlight. There was an architrave surround.21

The Prince now had leased all the 1,040 acre manor of Kempshott, together with the following appurtenances, legally summarized as: 2 messuages; 5 tofts; 1 malthouse; 6 barns; 6 stables; 1 granary; 1 dovehouse; 7 curtilages; 2 gardens; 2 orchards.

Preceding the formation of Kempshott Park, the component parts of the estate were: 740 acres of arable; 40 acres of meadow; 40 acres of pasture; 120 acres of wood; 100 acres of furze and heath, common of pasture and common of turbary.

The 45 closes within the Kempshott and Southwood Estates at this time can be identified as:

Sullingers, Bushy Plott, Little Heath, Great Heath, Long Close, Ox Leaze, Middle Meadow, Cow Leaze Close, Lower Meadow, Cow Leaze, Dial Post Meadow, Horse Coppice Meadow, Great Bottom Close, Three and Twenty Acres, Fourteen Acres, Little Bottom Close, Fry's Close, Ashendell Field, Hatch Field, Hogs Pasture, Calves Pasture, Red Yard Piddle, Ganderdown Close, Great Ramsholt, Upper Ramsholt, Lower Ramsholt, Deanheath, Salt Gate Piddle, Salt Gate Close, Hasket Field, Eighteen Acres, Clap Gate Close, Great Ashenrow Field, Little High Field, Great High Field, Little Ashenrow Field, Down Field, Southwood Green, Grubbed Ground, Picket Close, Rowdell Field, Great Birchen Close, Little Birchen Close, Barn Close and The Gate.

Kempshott Park, most likely, was formed from among the first 20 closes, excluding Sullingers and Bushy Plott.22

Kempshott Estate Plan, 1832

(H.R.O. 55 M67 T180-1)

This is the earliest finely detailed plan and largely unchanged from the time of the Prince of Wales' occupation.

(In 1788 there were 45 closes, reformed into 22 larger closes plus the Park between 1788 and 1830).

Kempshott House is to the lower right of the Prince of Wales' Feathers; Southwood Farm is to the upper right.

The Kempshott Kennel Gate stable block is to the lower left of the mansion house; the home farm is

south-east of the stable block (adjoining Kempshott Wood), incorporating the kennels.

The lands leased by the Prince from Thomas Terry in 1791 are within the area marked 'Stephen Terry Esq'.

Special Photographic Reproduction is by Courtesy of Hampshire Record Office

Having leased the Kempshott and Southwood Estates, the Prince felt encouraged to acquire further acreage nearer to Kempshott House. In 1791, also, he negotiated with Thomas Terry, lord of the manor of Dummer, for a lease of adjoining property, west of the Kempshott demesne, at an annual rent of £50 9s.7d. This consisted of lands known as:

The Drove and Great Picked Close (26:3:16), Earth Pits and Drove Piece (22:2:18), [leading to] Kembletons Bottom (27 acres), Great Rowley and one other piece (24.5 acres).

The total area amounted to 100 acres, 3 perches, 24 rods (1791 local measurement). The adjoining woods of Helworth Shrubs and Newly Coppices were also added.

All the specified lands had exclusive shooting rights. Leasing covenants applied for cutting and preserving hedges, keeping ditches, banks and fences in good repair, dealing with dung, safeguarding young trees from cattle damage and clearing underwood at specified intervals at Rowley, Helworth Shrubs and Stubs Coppice. The cutting of the underwood was to begin at Michaelmas and the produce to be taken off the premises on or before the 10 May following, failing which this work was to be carried out 'at the charge of the Lessee paying for the same after the Rate of 7£ an Acre'. There was also a ditch, which, being the legal boundary of Winslade and Dummer parishes, was to remain in tact. Timber rights remained with Mr Terry. The lease was to take effect from Michaelmas 1791, for '8 years... if HRH so long continues at Kempshott'.23 There is no evidence to suggest that the Prince leased any other adjoining realty.

Modern Day Entrance to Kempshott Park

Situated on lands leased in 1791 by the Prince of Wales from the Dummer estate.

During the nineteenth century both the Kempshott & Dummer estates were acquired by

Sir Nelson Rycroft, bt.

Photograph: Christopher Golding (October 2011)

Kempshott was now a quasi-royal estate. Nearby gentry and farmers must have reflected on the attraction and prestige of a potential invitation to the mansion house and of meeting the Prince informally. The attraction of Kempshott House to a flamboyant Prince of the Blood, however, is not immediately apparent. The mansion was a somewhat austere structure and typical of many mid to late eighteenth century smaller country houses. With its three storeys, though, Kempshott's exterior was certainly well proportioned showing to great effect the semi-circular bows centred in the north-west and south-east fronts. These rose the full height of the house. Attached to the north-west front, overlooking the Park, was a loggia of paired columns most likely of a dwarf Greek Ionic order rather than a Roman Doric order. This low colonnade supported a simple ornamental balcony, 8 feet wide, giving off the principal storey windows. From the top of the ironwork, to the floor of the balcony the measurement was 3-4 feet. The slender architrave windows were four feet in width on all three storeys, with the eleven feet high principal storey windows being nearly twice as high as those of the basement and bedroom storeys. The house had no attic storey.

The south-east front, overlooking the courtyard, was similar but with a rectangular portico, some eight feet wide, six to seven feet deep and ten feet high, attached to the front of the semi-circular loggia and providing access, by five or six steps, to the principal storey, with the door being some five feet wide. At either side of the loggia front were single supporting columns doubtless of a dwarf Ionic rather than a Doric order. The ornamented balcony was four feet wide at the bow and nearly six feet wide on each side. The east and west sides had four windows on each of the three storeys. All windows were sashed, with the possible exception of the ones on the principal and basement storeys, north-west front, which may have fully opened. The unornamented edifice is likely to have been composed of red face brick, brick makers doubtless having worked nearby - the name Brick Kiln Field appears on the early nineteenth century estate map. A simple modillion cornice defined the tops of both fronts, with parapets and coping above. The roof was almost certainly slated - often being used for roofs not intended to form a distinctive feature of the design. The roof was crowned with chimneys, which, at eye level, were aligned with the semi-circular bows. Kempshott House was nearly 68 feet wide, 50 feet deep (excluding the semi-circular bows) and nearly 45 feet high to the top of the parapet. The exterior and interior supporting walls were at least two feet thick.

The offices were situated at the south-east front and disposed about the mansion house in two quadrant wings with pavilions, consisting of basement and principal storeys only. At each of the wings' points of attachment to the house there was a formal entrance. This folded-wing arrangement was indicative of an owner of moderate fortune but sophisticated tastes - although the design was considered effective for the subsidiary residences of the very wealthy.

Kempshott House, North-West Front, late 19th/early 20th century

Pediments to the principal storey windows were added by 1833 at the latest. The ironwork ornamental balcony

above the loggia, which extended the width of the north-west front in the 18th century, was removed later in the 19th century and replaced with a solid balcony, limited to the bow, as part of major alterations/expansion to the house. The two single columns at the front supporting an extension to the balcony were also 19th century additions.

(See also Proposed Basement Storey Extension in Part III).

Image Reproduced by courtesy of Lost Heritage - England's Lost Country Houses

In 1795, Henry Holland, the Prince's architect, submitted designs for proposed alterations and extensions to Kempshott House. Such an undertaking strongly suggests an intention to purchase and to convert the place into a major subsidiary residence. Such a move, however, did not proceed and the proposed alterations remained unexecuted, discussed in Part Three. The most striking feature of Holland's elevation was the proposed construction of a pedimented wing on each side of the house. These were to be simple structures of three bays and on three levels consisting of basement, principal and bedroom storeys. A simple cornice was to define the pediments. A continuation of the central block - the existing house - ornamental balcony was to give off each of the pediments' principal storey windows, the central ones of which were to be contained within blank arches. The blank basement plinths were to be rusticated. An attic storey was proposed for the central block which would have raised the height of the house by some five to six feet, as a result of which a new roof and chimneys would have been required. The drawing suggests that stucco was to adorn the exterior walls. The pedimented wings were to remain, and with the addition of a bed chamber storey.24

Notwithstanding the non-execution of this proposed expansion to Kempshott House, his Royal Highness's comparatively modest but comfortable retreat was to provide him with some of the happiest years of his life. Furthemore, much of this time was to include copious hours in the saddle, devoted to his principal recreation: Hunting.

Copyright (c) 2013 Christopher Golding

|